|

| A solid gold bar. |

Thursday December 21, 2023.

It was a remarkably mild evening as Emma, Erin, Keilyn and I made our way from Watford to London, for the evening. Our plan had been to catch a fast train from Watford Junction to Euston, but problems with the overhead power cables saw us take the London Overground, instead. We changed to the Northern line, at Euston, and continued on to Bank station. This route put an extra twenty minutes-or-so on our journey, but we still made it in plenty of time.

Our reason for travelling to London, late on a Thursday afternoon... to see the Bank of England Museum and, hopefully, receive a bauble filled with shredded bank notes. The queue was already at the corner of Threadneedle Street and Princes Street, so that's where we joined it. The time was just after 16:30.

|

| We have joined the queue. |

We chatted to other people in the queue, plus those who stopped to ask what we were all queuing for, as we passed the time. Slowly, very slowly, the train of people began to move as 17:00 arrived and the doors to the museum opened. All the while Erin was keeping her eyes peeled, in case she spotted the ghost of Sarah Whitehead, who is said to haunt Threadneedle Street. We saw no sign of her.

|

| Keilyn standing in an alcove, outside the Bank of England. |

However, due to the capacity of the museum, only small groups were able to enter at a time.

By now the queue behind us had travelled the length of Threadneedle Street and up Princes Street, around onto Lothbury and then across the road to Throgmorton Street. One of the museum staff had estimated that there were nearly 2,000 people in the queue, at one point.

As the time approached 18:30 we found ourselves at the front of the queue, only to be told that the museum had run out of baubles. They had thought that 500 would be enough, as only 250 people had turned up in 2022.

A little disheartened we still entered the museum and had a great evening learning about its history, lifting a gold bar (that weighed 13kg), and generally having a good exploration of the place.

|

| 'Carols Round the Tree' songbook. |

Unfortunately, we missed the 'Carols Round the Tree', but there were still refreshments being served.

|

| Erin sitting on a £1,000,000. |

Not only does the museum tell the history of the Bank of England, it also holds exhibitions in the Rotunda.

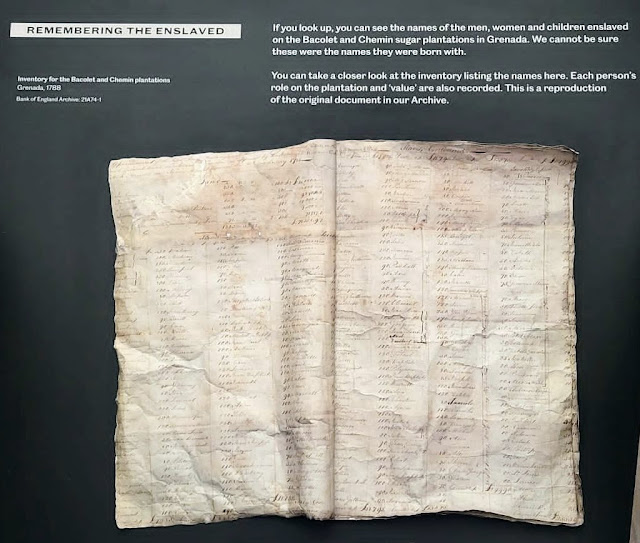

The current exhibition is entitled 'Slavery & The Bank', which explores the links between the slavery and the Bank through the private business of these Bank officials, and the Bank's place in the wider financial system at the time. It also highlights the Bank's ownership of two sugar plantations in the late 1700s and the enslaved people who worked there.

|

| Inventory for the Bacolet and Chermin plantations, Grenada, in 1788. |

Suitably satisfied we made our way out of the museum, to find the queue, which had shrunk considerably, was still formidable.

We decided to head towards Liverpool Street station, via Old Broad Street, where Keilyn spotted an old Police Public Call Post, one that I had not seen, so I took a photo of her with it.

|

| Keilyn with a City of London Police Public Call Post. |

After eating some food, at Liverpool Street station, we headed down to the underground station and waited for a train home.

|

| The Great Eastern Railway Memorial at Liverpool Street station. |

Next year, if it happens again, I shall book the day off work, so that we can be nearer the front of the queue, ensuring our chance of receiving a bauble filled with shredded cash.

Brief History

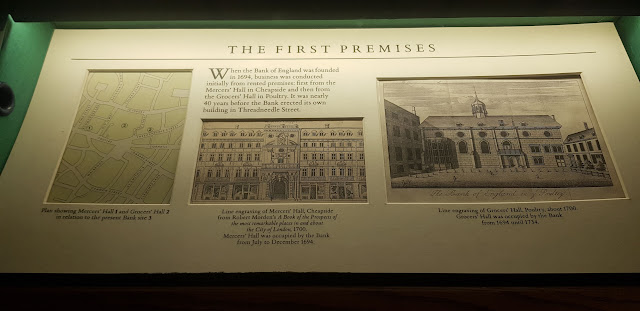

The Bank of England was founded in 1694 to raise money during a time of war against France. It was established by Royal Charter and began as a private bank. Money was raised from private investors and lent to the government.

|

| The First Premises. |

After spending its first 40 years in rented premises, the Bank moved to its own building on Threadneedle Street in 1734. The Bank grew steadily in size and importance, and by the 1790s it was firmly established as the government's bank, managing the national debt.

The French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars (1789-1799 & 1803-1815 respectively) had a serious effect on the economy. In 1797, the Bank had to stop paying customers in gold for its notes in order to maintain sufficient gold reserves. This was a very controversial move. The Bank's famous nickname 'The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street' comes from this time. The satirist James Gillray was one of the first people to use this nickname, in a 1797 cartoon on display in the Bank of England Museum.

During the 1800s, the Bank continued to grow and solidify its position as the nation's bank. This role increased even more during World War I, when the national debt surged dramatically. The Bank's old buildings had become too small for all of its staff. And so, between 1925 and 1939, the Bank was entirely demolished, rebuilt and expanded by the architect Sir Herbert Baker.

The statues around the Rotunda, called caryatids, were original features in Sir John Soane's Bank. They were salvaged for use in the new building when the old Bank was demolished.

|

| A Caryatid. |

The Bank took on the functions of a modern central bank during the interwar years, managing the country's gold and foreign exchange reserves and executing monetary policy. This role was formalised when the Bank was nationalised in 1946.

Today, the Bank of England stores gold for the UK Treasury, other governments, and central banks around the world.

Trivia

- The 'Promise to Pay' has featured on Bank of England notes since 1694.

- The first monarch to appear on Bank of England notes was Queen Elizabeth II, in 1960.

- The first historical character to appear on Bank of England notes was William Shakespeare, in 1970.

To find out more about the Bank of England and its exhibitions click the link below.

No comments:

Post a Comment